Perfectly Safe Deposits and Robust Lending: Splitting Deposit Banks from Lenders

It doesn’t have to be this way

This post has to begin with a stipulation: Perfectly safe bank deposits are a public good. Your bank will never tell you that you have less deposits because the bank has financial difficulties. A $1 transfer to another bank will always be accepted and deposited at par: $1. The manifest benefits of that situation are taken as a given here.

The U.S. government financial powers-that-be clearly agree: they’ll do whatever it takes to guarantee that public good. If 2008/9 didn’t sufficiently demonstrate that reality, recent bank events certainly have. (Insert innumerable institutional acronyms here — FDIC, FSLIC, FHLA, BTFP, The Fed of course, and very much including the U.S. Treasury.1)

The takeaway reality is well-stated in Steve Randy Waldman’s (@interfluidity) post title: “Banks are not private.”2 By refusing to acknowledge that, we end up with implicit deposit guarantees, a Rube-Goldberg mishmash of government institutions, and assorted ad hoc interventions.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

Pure Platonic Form: Fed Checking Accounts

On its face, the simplest imagined alternative is to acknowledge the reality — deposit liabilities are ultimately Fed & Co. liabilities — and give everybody (people and firms) checking accounts at the Fed. People moving their deposits to other banks in a “run” isn’t a problem; there is no other deposit bank.

Even if everybody wanted to swap their deposits for physical cash (yeah, as if…3), the Fed plus the Bureau of Printing and Engraving could accommodate that with their normal operating procedures. (Though sure, not overnight, but everyone knows they could do it.) The deposit liabilities, now explicitly on the right side of the Fed’s balance sheet, would be purely notional; deposits could only be “redeemed” in the form of…deposits.

But today’s banks have another “essential” function besides managing deposits: lending. If you think that deposits “fund” lending, this hybrid deposits-and-lending setup seem inescapable and inevitable. But that thinking is based on a dismayingly ubiquitous misunderstanding: that saving creates deposits a.k.a “loanable funds.” It doesn’t. Lending by Fed-chartered banks creates deposits.

We could, and arguably should, split these two essential functions into separate institutions: deposit banks, and lenders (we won’t even call the latter “banks.”) When lenders lend, the new deposits go into the borrowers’ accounts at deposit banks. The lenders aren’t custodians for those deposit balances.

The Word is Out

This is not radical thinking these days. As in the post-GFC era, over the last month there’s been a surge of financial and monetary experts across the institutional spectrum bruiting this kind of sensible, coherent alternative. We’re hearing clearly stated understandings that have been fighting for wide acceptance for decades — really more like a century. (Much credit to MMT for spearheading that.)

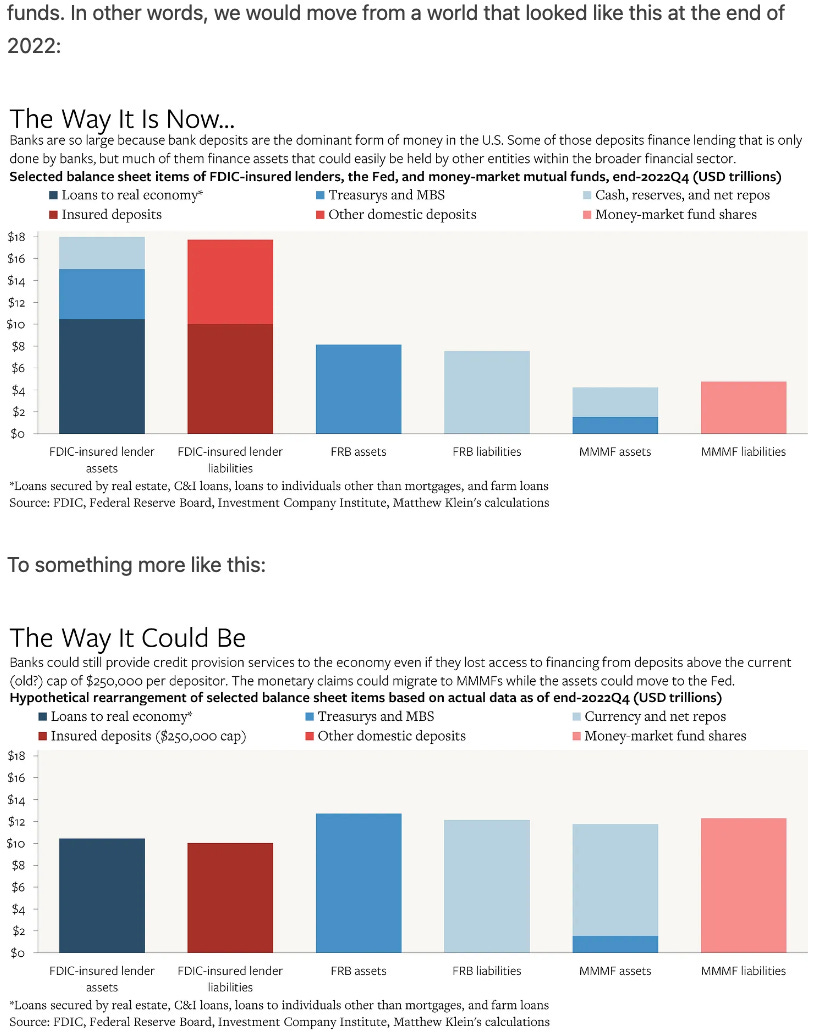

Matthew Klein offered one carefully worked-out alternative a month ago. It’s a step toward explicit Fed banking, without going full-frontal.

This picture retains our current “hybrid” deposits-and-lending commercial banks, but reduces them to those two elemental functions: their only assets are “real-economy” loans receivable. Deposits are their only liabilities, and those are ultimately FDIC (and Fed etc.) liabilities.

Money-market funds become pure deposit institutions. (Though the deposits are fixed-price “fund shares”; they still quack like a duck.) Their assets are pure Fed and Treasury issues. (The “currency” item is effectively Fed reserve/deposit holdings but held at one step remove, via the funds’ “correspondent” banks. The repo assets are direct, via funds’ own explicit Fed repo accounts.)

This would be a big step toward making the implicit explicit, acknowledging and rationalizing the actual “public” nature of banks (and MMFs), and reducing the dizzyingly complex and opaque financial “de-risking” mechanics behind current MMFs. (See Zoltan Pozsar, 2011.)

But what if we fully reject the arithmetically incoherent notion that “saving creates deposits which fund lending,” and entirely separate deposit banks from lenders? Split today’s commercial banks down the middle, with both sides under the purview of the Fed and allied institutions:

Fed-chartered deposit banks are basically sub-contractors to the Fed, managing depositors’ bookkeeping, transfers, online access, and retail locations for a fee paid by the Fed as public good, by depositors, or some combination. (Compare recent years, where banks pretended to pay interest, and depositors pretended to get free account services.)

Fed-chartered lenders (again, we won’t even call them banks) have the special privilege of creating new deposits for lending, as Fed-chartered banks do now. But the new deposits aren’t “held” by the lenders; they’re issued directly into (separate) deposit-bank accounts.

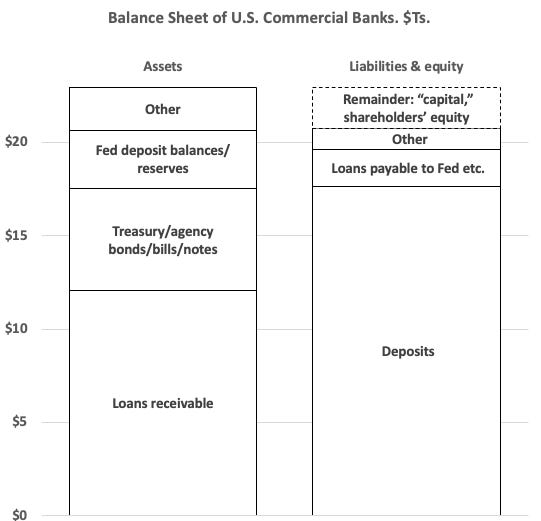

Here’s what that looks like in balance-sheet form:

The Way It Is Now

A mix of various assets and liabilities.

Come da Revolution…

Here’s one way pure deposit banks might look in the Brave New World: they actually “hold” customer’s deposits as liabilities in for-benefit-of (FBO) custodial accounts, offset by Fed reserve deposit assets (which are explicitly liabilities of the Fed). This is basically what people call “narrow banking.” These banks keep the detailed tallies of customers’ deposits and transactions, not the Fed. It’s Fed banking, but again one step removed.

Even simpler (though not necessarily preferable), the Fed could maintain the tallies of individuals’ accounts, and the deposit “banks” would just provide the user interface for managing those accounts — services, online access, retail branches, etc. (The Fed would provide an API for use by these chartered entities.) As mere fee-for-service firms, the balance sheets of these companies would be tiny: some operating cash/bonds and infrastructure (servers, retail branches, etc.) on the left side of the balance sheet, and maybe some private loans- or bonds-payable, plus residual shareholder equity, on the right side.

In either case, this makes all deposits perfectly safe. (It might also make money-market funds obsolete.)

What would the new Fed-chartered lenders look like?

They borrow from the Fed, and make a profit by lending at higher rates. Like current banks, their borrowing rights from the Fed confer the special privilege of creating new deposits for lending. (The new deposits go straight into FBO accounts at deposit banks.) As with today's banks, the lending decisions would be outsourced by the Fed to these private entities under the assumption that their profit incentives will result is smarter lending decisions. (Private lenders and lending funds would of course still exist. But they don’t create new deposits; they just move existing deposits around.)

This seems pretty radical, but before making objections I encourage my gentle readers to think it through carefully. Most of them are easily addressed, while others would require some institutional reform (which certainly might encounter institutional/political resistance).

Consider also the very large potential benefit: a big, broad, diverse ecosystem of expert, specialized, bespoke lenders displacing the big, dumb, assembly-line banks-cum-lenders that currently dominate the landscape. That needs more explaining; to keep this post short, for now I’ll farm that explanation out to Steve Randy Waldman, with some small edits.

Banks should fail much more often

If the state is financing credit and investment funds [it is, currently, in a very big way], they should be small, undiversified specialist funds. … The state’s interest is to hire the most informationally qualified people to invest in a particular domain — which might be an industry, a locality, or type of borrower — and then to incentivize them to invest as well as they are capable within that domain. … The state would finance many little

banks[lenders] across a huge range of domains (industries, locations, borrower types), and end up with a diverse[ified], high-performance development portfolio.

The simplified (balance-sheet) picture in this post is at least a useful thought experiment, and platform for thinking through alternatives to the current mish-mash of institutional systems. There are innumerable issues to discuss, and I look forward to hearing the thoughts of my gentle readers.

Example: When the $65-billion money market Reserve Fund/Primary Fund (not insured by the FDIC/FSLIC or any private bank-insurance institutions) “broke the buck” on September 15, 2008, only offering to transfer 97 cents to commercial banks for $1 in money-market deposits (“shares”), the U.S. Treasury stepped in within 48 hours to guarantee and prop up the $1 share price of all money market funds. (The funds paid a fee for this temporary but mandatory insurance, dissolved in September 2009.)

Many thanks to Steve for many fruitful discussions over many years, including much recent help with the balance-sheet logic here.

Physical currency, mostly held as $100 bills in suitcases in Colombia, Russia, etc., is trivial in quantity and has ~zero import for the financial/monetary system.