Trade Balances: It’s the Spending, Stupid

The obsession with measuring “production” results in strange misunderstandings.

This post is dedicated to my sister, who (bless her heart) really follows the financial press and etc. and tries to understand things. She called me up kind of flummoxed by all this tariff/trade talk recently, and now IMO has a super-good basic understand of imports, exports, GDP, etc.

Noahpinion does yeoman’s work here and here, beating a horse that just won’t die: the idea that “imports reduce GDP.” But he hardly ever uses the simple word that makes it all really easy to understand: spending.

So understand first: the “real-world”1 thing that national accountants actually measure and observe is not “production.” They tally up spending. (Precisely: “final” spending on newly-produced goods and services. Firms’ spending on inputs to production aren’t included because you’d end up counting the inputs twice — when the firm purchases them, and when people purchase them again as part of the final goods.)

Production is just imputed from spending: “If people spent $1T on widgets, the produced widgets must have been worth $1T.” That’s not crazy; how else are you gonna sum up a quantity for a zillion different things that get produced — drill presses + massages + lines of computer code? And if you’re gonna tally that in dollars, price paid is probably the about best “value” estimate you can use.

But economists constantly treat that accounting estimate of production as the “real” ultima thule at the tippy-top of the national-accounting pyramid: GDP. This results in some weird conceptual errors and confusion like the ones Noah rails about (arguably at unnecessary length).

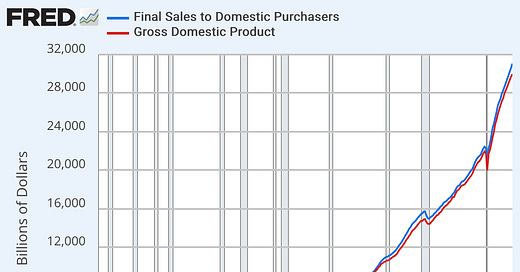

The funny thing is, you never see a labeled headline measure of the thing that actually gets measured or observed: Gross Domestic Spending (GDS). But it’s easily available: Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers (FSDP). It’s almost identical to GDP; the discrepancy is just the trade imbalance.

Here’s the simple understanding to estimate US production from actual measured spending:

Tally up US total spending on new final goods and services. FSDP.

Subtract spending on goods and services that were not produced in the US. Imports.

Add other countries’ spending on goods that were produced in the US. Exports.

You’re done.

Next, here’s an economic claim: spending is arguably the driving force and lifeblood of “the economy.” It’s the material real-world expression of people’s desire for goods and services (at a given price point). And spending is what causes production. (Ask any producer why they produce stuff.) So if you just want a single general metric of the size, growth, and general strength of a country’s economy, why not just use spending in the first place?

Joey Politano gets it. Here’s the final “money graph” from his latest post. Note that this measure isn’t subject to the big quarterly swings that GDP is, because it’s not trying to estimate production; it’s just showing spending. It uses the “real” (inflation-adjusted) measure versus nominal, but whatever; it’s easy to convert between those, and absent big changes in the inflation rate it doesn’t make much difference for the trend.

Economists also (often) use spending and “demand” kind of interchangeably, saying “demand increased” when they observe increased spending. But they should know better than anyone that demand is a curve, not a quantity. This kind of thinking also plays out when thinking about trade balances.

Let’s say total spending is a measure of total demand, for instance. Then you can think about imports as demand that “leaks out of the economy” to other countries. You even hear it described as “exported demand.” (Or if you’re Trump, “stolen.”) While exports are “imported demand.” But that thinking has an assumption baked in: that domestic producers would have provided the imported stuff, “gotten the demand,” if other countries hadn’t. It’s not nutty, but it’s very stylized thinking. If you want to think about things this way, you have to be careful to check and interrogate your (unconscious?) assumptions at the door.

In the meantime the general public, at least, can relieve its mental burden a lot if they start with the simple economic dictum: It’s the spending, stupid.

I don’t even touch here on a separate meaning of real: “inflation-adjusted.” A separate can of worms.…

Nicely said